Windletter #112 – Floating wind needs pre-commercial wind farms

Also: the Luxcara–Mingyang project under scrutiny, the first commercial Vestas V172-7.2 MW units, the video that lets you see wind turbine wakes, and more.

Hello everyone and welcome to a new issue of Windletter. I'm Sergio Fernández Munguía (@Sergio_FerMun) and here we discuss the latest news in the wind power sector from a different perspective. If you're not subscribed to the newsletter, you can do so here.

Windletter is sponsored by:

🔹 Tetrace. Reference provider of O&M services, engineering, supervision, and spare parts in the renewable energy market. More information here.

🔹 RenerCycle. Development and commercialization of specialized circular economy solutions and services for renewable energies. More information here.

🔹 Nabrawind. Design, development, manufacturing, and commercialization of advanced wind technologies. More information here.

Windletter está disponible en español aquí

Last call to vote for me for the “Best Energy Communicator” award, organized by El Periódico de la Energía.

To cast your vote, simply enter your email address in the form at this link. You’ll then receive an email with a link to confirm your vote.

Thank you all so much for the support!

The most-read pieces from the latest edition were: the video of Dongfang’s 153-meter blade, the video of the Aikido One floating platform, and the first SG5.X turbines installed in Spain.

Now, let’s dive into this week’s news.

🌊 The value of pre-commercial projects in floating wind

Almost all the floating wind capacity currently installed worldwide corresponds to pre-commercial projects. These serve as an intermediate step between a prototype and a large-scale wind farm (hundreds of megawatts), allowing the technology to be tested under real-world conditions and scale.

This stage is particularly important for a technology that is still under active development, where hands-on experience and learning can play a critical role.

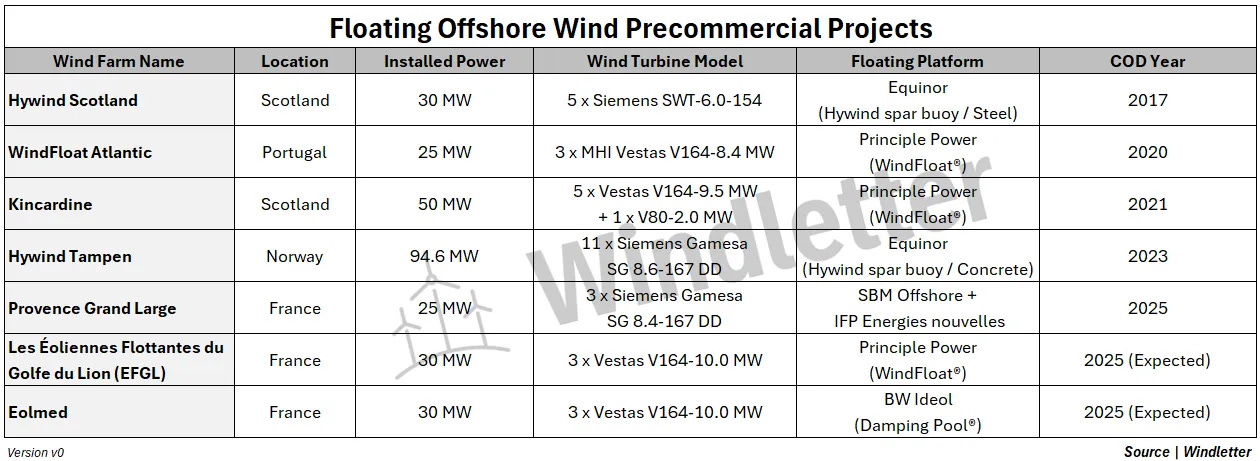

If we look at the global track record of floating wind, these early-stage projects typically feature between 3 and 11 turbines, each ranging from 6 to 10 MW, although 3-turbine setups are by far the most common.

I’ve compiled the existing and upcoming projects in the table below (and if you spot any errors, feel free to let me know 🙂).

A notable feature is the diversity of floating platforms, a clear sign that the market is still searching for the best technologies.

Industry experts predict that, in the future, only 2 or 3 floater designs will survive, those that can demonstrate operational experience, reliability, and competitive CapEx and O&M costs.

👉 On the topic of maintenance operations in floating wind, I found this piece from Spinergie particularly interesting.

If we zoomed in further, we’d likely see a variety of mooring systems, dynamic cables, and many other competing technologies, all aiming to become industry standards.

In this regard, Carlos Martin Rivals, former BlueFloat Energy executive and now General Manager for floating structures in Europe at Dajin Offshore, recently shared an insightful article on LinkedIn, highlighting the importance and value of pre-commercial projects.

It might sound like hindsight, but I’ve genuinely always believed that these kinds of projects are essential as a stepping stone toward large-scale floating wind.

As Carlos points out, they are especially valuable for improving reliability, reducing costs, developing the supply chain, and enhancing, or even enabling, bankability.

In fact, if we look back, it’s something we discussed in Windletter #11 (July 2022) when Saitec Offshore submitted two 45 MW projects (3 x 15 MW each) in Spain.

To this day, I still don’t understand why Spanish public institutions never supported such initiatives. They could have helped boost local R&D, engineering, and supply chains, and increased public awareness of the technology during times of opposition. All at a reasonable price. Portugal did it five years ago with WindFloat Atlantic.

The delays in current auctions (despite recent talk that they may still be held this year) would have been easier for the industry to endure. In fact, the ongoing uncertainty has already led some developers to exit the Spanish market.

Another key issue is turbine supply. According to industry sources, Western OEMs show little interest in offering their turbines for floating projects. After all, floating versions often require further development and, more importantly, involve higher risks in terms of maintenance, warranties, and serial defects.

SGRE and Vestas already have their hands full with the development and monetization of their fixed-bottom offshore pipelines through 2030–2032, over 30 GW between the two, so floating wind is not exactly an attractive proposition right now, especially after several turbulent financial years.

What’s your take on all this?

⚠️ The German government may cancel Luxcara’s offshore project involving Chinese wind turbines

Nearly a year ago, we reported that German developer Luxcara had selected Mingyang as the preferred supplier for the 296 MW Waterkant offshore wind farm in Germany.

It was a headline-grabbing move that quickly spread across the industry and made waves in the press. Luxcara publicly defended its decision, stating that Mingyang had been chosen following a due diligence process supported by DNV and KPMG, which covered the supply chain, ESG compliance with the EU taxonomy, and cybersecurity.

However, Germany’s Ministry of Defence has now raised serious concerns about Mingyang’s involvement in the project. According to Offshore Magazine, the concerns stem from a report by the German Institute for Defence and Strategic Studies (GIDS), which was submitted to the Ministry of the Interior.

The report argues that, in a scenario of deteriorating diplomatic relations, China could leverage its control over the turbines to delay projects, access sensitive data, or even remotely disable the wind turbines.

This comes amid broader scrutiny, as the European Commission launched investigations over a year ago into Chinese manufacturers over suspected unfair competition.

The report suggests excluding Chinese firms from the project using legal instruments such as Germany’s public procurement law or the Wind Energy at Sea Act.

Meanwhile, PeakLoad has reported that Luxcara is currently seeking co-investors for the Waterkant project and for another 1.5 GW offshore project—Waterekke—in the German North Sea.

🌍 Mingyang begins wind turbine installation in Serbia as Sany signs new contract

Continuing with Mingyang, the manufacturer recently announced the start of installation at the Serbia Black Peak wind farm, where it is supplying 25 units of its 6.25-172 model.

As shown in the photo, and as we mentioned in the previous edition, there is once again a notable coincidence: both the turbine manufacturer and the project developer are Chinese (in this case, SPIC). This is part of a broader strategy that Chinese OEMs are using as a gateway into Europe, entering various markets by promoting their own projects.

It’s also worth noting that Mingyang turbines feature Super Compact Drivetrain technology, which we covered in more detail in Windletter #69.

Mingyang, in fact, has a long-standing presence in Eastern Europe, having supplied turbines to the region 12 years, starting with a wind farm in Bulgaria.

Almost simultaneously, Sany announced the signing of a PPA and CfD for its 168 MW Alibunar wind project, also located in Serbia.

At first, the news was puzzling. Why would a turbine manufacturer sign a PPA? But after a bit of digging, it turns out that Sany acquired the project from Norwegian developer Emergy in February this year.

Once again, it seems that Sany has adopted a strategy of becoming the project developer in order to accelerate its entry into the European market: my project, my turbines.

Sany has not disclosed which turbine model will be installed, but a report published on Emergy’s website in October 2022 mentions Vestas 4.2 MW turbines.

All in all, Serbia is becoming the main entry point for Chinese turbine manufacturers into the European Union, with wind farms already equipped, or soon to be equipped, with turbines from Windey, Mingyang, and now Sany.

🏗️ Vestas installs first commercial V172-7.2 MW EnVentus turbine

Vestas has announced on LinkedIn the installation of the first V172-7.2 MW turbine from its EnVentus platform. With a hub height of 175 meters, the turbine was installed in Salzkotten, Germany.

Please, no offense to anyone at Vestas, but I can’t help noticing that the asymmetrical nacelle catches the eye a bit 😅. We’ve become so used to perfectly symmetrical nacelles that this design seems to break the visual harmony.

But to be fair, wind turbines weren’t made to be pretty. They were made to deliver clean, reliable, and affordable energy.

And I fully understand that the design is like this for sound reasons. In fact, I find Vestas' approach very interesting and innovative.

This turbine is based on the modular design concept of the EnVentus platform, which we briefly analyzed back in edition #14 (feels like ages ago!) when the V236-15.0 MW nacelle prototype was first introduced.

The idea is to house key components in standard shipping container-sized modules. The module you see on the right side of the nacelle in the photo contains the electrical cabinets, converters, and the transformer.

And I’m almost certain (though I can’t confirm it) that the 15 MW model has two identical containers, one on each side, each carrying the same components (essentially 7.5 MW per container).

This modular approach brings a major advantage for Vestas: it allows each module to be manufactured independently, possibly at different factories, and shipped separately without requiring special transport. On-site assembly then becomes a plug-and-play process, something that’s clearly shown in the video below.

In the case of onshore turbines, the other side of the nacelle is designed with space reserved for additional equipment, such as a crane, a battery, or even an electrolyzer.

You can read more about the V172-7.2 MW at this link.

🌪️ The video that lets you see a wind turbine’s wake with your own eyes

I really enjoyed this video I came across on LinkedIn, where, on a rainy day, you can clearly see the wake created by the turbine blades as they move through the wind.

The raindrops reveal the spiral pattern left behind in the air, making the phenomenon visible to the naked eye.

It’s also worth noting that the turbine shown in the video is a direct drive model from Brazilian manufacturer WEG, a company we’ve mentioned several times for its plans in Brazil, the United States, and India.

Thank you very much for reading Windletter and many thanks to Tetrace, RenerCycle and Nabrawind our main sponsors, for making it possible. If you liked it:

Give it a ❤️

Share it on WhatsApp with this link

And if you feel like it, recommend Windletter to help me grow 🚀

See you next time!

Disclaimer: The opinions presented in Windletter are mine and do not necessarily reflect the views of my employer.