Windletter #111 - Dongfang tests the 153 meters of the largest blade in the world

Also: another new manufacturer in India, Aikido to install a 15 MW prototype in Norway, Shanghai Electric installs its first wind farm in Europe, and more.

Hello everyone and welcome to a new issue of Windletter. I'm Sergio Fernández Munguía (@Sergio_FerMun) and here we discuss the latest news in the wind power sector from a different perspective. If you're not subscribed to the newsletter, you can do so here.

Windletter is sponsored by:

🔹 Tetrace. Reference provider of O&M services, engineering, supervision, and spare parts in the renewable energy market. More information here.

🔹 RenerCycle. Development and commercialization of specialized circular economy solutions and services for renewable energies. More information here.

🔹 Nabrawind. Design, development, manufacturing, and commercialization of advanced wind technologies. More information here.

Windletter está disponible en español aquí

The most-read pieces from the latest edition were: the images of the SG21.5-276, the video of the Tahivilla wind farm repowering, and optimizing offshore wind farm layout with machine learning.

Before diving into this week’s news, I’d like to ask you a small favor. Our sponsor RenerCycle has been nominated for the RSCapital Awards, which aim to highlight companies and organizations from Navarre that stand out for their commitment to sustainability, governance, and social action.

The winner is chosen by popular vote and, aside from truly deserving it, supporting them would be a great way to show appreciation for their support of Windletter. You can vote for them through this link.

📏 The 153 meters of the largest wind turbine blade in the world, put to the test

Dongfang Electric (DEC) has unveiled the largest wind turbine blade ever manufactured worldwide. With 153 meters in length and an estimated weight of around 70–90 tons, this blade is intended for the Dongfang Electric H2X000-31X model, with a rotor diameter exceeding 300 meters and a rated power of 26 MW.

The Chinese state-owned giant has shared an interesting video (via Gang Wang) showing the manufacturing process. We’ve translated the video with AI in a reasonably acceptable way:

The size of the mold is truly impressive, as is the amount of manual labor and craftsmanship involved in making a blade like this. Also, and why not say it, the way the video is edited is quite curious 🙃

If I’m not mistaken, the previous record was held by the 147 m blade from Sinoma, manufactured for Goldwind and its GWH300-20/25MW model. Of course, we also covered that blade in Windletter a few months ago.

It’s very interesting to see that, although Dongfang hasn’t been one of the leading players in Chinese offshore wind so far, it seems determined to lead the technological race to build the largest wind turbine in the world.

In this case, Dongfang has chosen to follow a relatively open communication policy, also sharing images of the static tests required by IEC 61400-23. Quite the testing bench.

According to experts in the sector about this blade:

It’s good that they’ve passed the tests required by IEC 61400-23 for blade certification, but this is only the first step toward having a robust product.

Manufacturing a blade of this size is extremely complex, with a very high level of manual work, as seen in the video, with dozens of workers laying materials by hand.

Honestly, I see a lot of risks in developing a blade of this size. Any field issue will cause OPEX to skyrocket.

On the topic of blades, the same Gang Wang also shared another video showing loading operations at a Chinese port for a set of blades for the Vestas V236. These blades were manufactured by Aeolon, another major Chinese manufacturer, but it’s unknown which project they are intended for.

The video caught me by surprise, as Vestas produces this model in Taranto (Italy) and Nakskov (Denmark). It seems the company needs to diversify its production due to the backlog of orders.

We’ll try to keep an eye on future developments.

🌍 Venwind, another wind turbine manufacturer enters India

As we’ve mentioned before in Windletter, India is one of the most competitive wind energy markets in the world outside of China.

It is undoubtedly one of the markets with the highest number of active manufacturers, a space where companies from all over the world compete, including many local firms.

The list of players is extensive. Some are well-established, others newly arrived. Among them: local companies like Suzlon, Adani, and Inoxwind; Western players like Siemens Gamesa (following its recent sale), Vestas, and General Electric; Chinese companies like Envision and Sany; and even the Brazilian WEG is trying to secure its share of the market. And I’m surely missing a few.

The truth is that, at present, India is not yet a huge market, with just 3.42 GW installed in 2024 (the fourth largest globally), but it undoubtedly has massive potential—being the most populous country in the world, with growing electricity demand and a vast territory.

Given these growth prospects, new players continue to enter the Indian wind sector. The latest is Indian group Refex, which, through its new subsidiary Venwind Refex Power Ltd, plans to invest ₹800 crore (~€87 million) in a plant to manufacture 5.3 MW wind turbines.

The project is based on a licensing agreement with Vensys Energy AG (Germany), which for many of you will be a familiar name. It’s a German company historically focused on technology licensing. Interestingly, Goldwind entered into a technology licensing agreement with Vensys in 2003, which allowed it to grow until 2008, when the Chinese firm bought 70% of the German manufacturer/technologist. You can read more about Vensys here.

This is not a random collaboration: Madhusudan Khemka, former founder of the now-defunct manufacturer ReGen Powertech (which also worked with Vensys), has played a key role in the alliance and is now advising the new company.

As for the 5.3 MW wind turbine, we know it will be based on the so-called “hybrid technology”, meaning a permanent magnet generator with a medium-speed gearbox. It’s the same configuration used by Vestas in its EnVentus platform and by many Chinese OEMs, including Goldwind.

Their website also directly references the GWH182-5.3 MW model, which means a 182-meter rotor diameter, very likely the largest offered in India. You can find the catalog here.

Another conclusion I draw from this news is that Goldwind, for now, doesn’t appear to be interested in entering the Indian market directly. Otherwise, it wouldn’t make sense to license a technology it owns to a potential competitor.

🎉 Goldwind celebrates 2 GW installed in South America

Chinese manufacturer Goldwind has surpassed 2,000 MW of installed wind capacity in South America, its longest-standing international market outside of China.

The story began in 2008 with the Gibara 1 wind farm in Cuba, a pioneering 4.5 MW project made up of six GW50 turbines rated at 750 kW. It was the company’s first wind farm outside its home country. Right next to it, the Gibara 2 project was built, equipped with six Gamesa G52 turbines of the same rating.

Just a year later, in 2009, Goldwind began operations in the United States and Australia as well.

Since then, growth hasn’t stopped. In Chile, Goldwind has installed 706 MW since signing its first project in 2011 (operational since 2013). The fleet includes 250 MW of GW155 and 342 MW of GW165, in projects with clients such as Enel, Engie, and Mainstream. Recently, contracts have also been signed for turbines like the GWH170 (7.2 MW) and GWH182 (7.5 MW).

In Brazil, total installed capacity exceeds 900 MW. As previously mentioned in Windletter, in 2023 Goldwind inaugurated its factory in Camaçari (Bahia), with the capacity to produce 500 wind turbines per year. In total, the Chinese OEM has around 2 GW in operation and construction in the country.

In Argentina, there are 354 MW in operation (GW140) and another 378 MW under construction, with a target of reaching around 720 MW connected.

Lastly, Goldwind also has a presence in Bolivia (3 MW) and Ecuador (16.5 MW), as well as in Panama, where it has installed 270 MW.

🛠️ The first Siemens Gamesa SG5.X turbines installed in Spain

Siemens Gamesa is taking longer than expected to return to the onshore market with its 4.X and 5.X wind turbines. Both models were pulled from the market more than a year and a half ago due to quality issues, and no new orders for these platforms have been announced since.

On the one hand, the 4.X platform officially resumed commercial activity last September, but has yet to secure any new orders. According to Christian Bruch, CEO of Siemens Energy, the reactivation of orders "is taking longer than expected."

On the other hand, the 5.X platform remains in the redesign phase, though it is expected to return to the market later this year.

However, despite this situation, Siemens Gamesa's onshore activity has not come to a halt. The company has continued delivering and installing turbines (very likely after completing the necessary retrofits) to meet various existing customer commitments.

In fact, I recently came across photos on LinkedIn of 5.X turbines being installed in Germany and other parts of Northern Europe. And more recently, in Spain as well—specifically at the Cluster Cerrato wind farms in Baltanás (Palencia), where 6 SG4X and 19 SG5X turbines are being installed, the latter being among the first of their kind in Spain.

Additionally, Iberdrola recently announced the resumption of works at the Iglesias wind farm, which will also feature the SG5.X model.

🌊 Aikido Technologies to install a 15 MW prototype of its floating wind technology

Aikido Technologies is a U.S.-based startup founded in San Francisco in 2020 and backed by Bill Gates through Breakthrough Energy Fellows, a fund focused on innovation in the energy sector.

The startup’s mission is to develop a floating wind platform aimed at revolutionizing the market by reducing the cost of the technology.

Last December, we reported on how Aikido had built its first 1:4 scale prototype, the Aikido One, an experimental platform designed to support a 100 kW wind turbine.

Aikido is now preparing to take the next step in developing its platform with the announcement of a 15 MW demonstration project at the METCentre (Marine Energy Test Centre) in Norway. The METCentre is one of the most advanced floating wind testing facilities in the world, where technologies such as Hywind Demo, Google Makani, Stiesdal’s Tetraspar, and the upcoming SeaTwirl have been tested.

Once installed in 2027, this platform, named AO60, will be one of the largest ever deployed in floating wind. Remember, most of the currently installed parks and prototypes remain below the 10 MW mark.

Aikido’s platform is composed of thirteen modular steel components that can be fabricated at existing offshore wind or steel structure facilities. For the AO60 project, the components will be transported to a final assembly site near the test center, where the platform can be fully assembled in a matter of days—not months, as is typical with other floating platforms.

Personally, I find the concept interesting—disruptive innovations are certainly needed—but as with other floating platform concepts, I believe one of the major challenges lies in “convincing” wind turbine manufacturers to adapt their designs to the platform.

In fact, I find myself wondering: whose turbine will be installed on this 15 MW platform?

🔍 Senj Wind, the Croatian wind farm with 39 Shanghai Electric turbines

Thanks to a LinkedIn post by Jiangsheng Zhu, Business Development Director at Shanghai Electric, I came across a very interesting story.

According to the post, Senj Wind the first (and possibly only) Shanghai Electric wind farm in European territory, has reportedly reached full return on investment after just three years of operation (we’d need to dig into the fine print on that). Additionally, according to the same post, it has maintained a 99.8% availability rate so far in 2025. An impressive figure.

But what’s most interesting isn’t the numbers it’s the story behind the project. I did some digging and ended up uncovering a rather curious background.

First, the owner of the wind farm is Norinco International, a Chinese state-owned conglomerate active in numerous sectors. It’s interesting to consider how the opportunity to invest in a Croatian wind farm even came about.

Most likely, this ownership paved the way for the turbines to come from Shanghai Electric. It’s a strategy we’ve seen elsewhere: investor and technology from the same country, such as SPIC and Goldwind in Brazil.

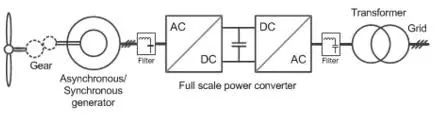

The 156 MW wind farm is made up of 39 EW 4MW-136 turbines. These turbines use a drivetrain configuration based on an asynchronous generator + gearbox + full converter, the same type used in Vestas’s 4 MW platform.

Some of you may also recall this configuration from the “geared” turbines of the former Siemens Wind Power (known as the G2 and G4 platforms), which SGRE still sells in the United States today.

Here’s where it gets even more interesting: Siemens Wind Power and Shanghai Electric began cooperating in 2011, establishing a joint venture that marketed turbines based on Siemens technology. That joint venture later evolved into a licensing agreement.

One of the first turbines under that deal was the SWT 4.0-130 (which still appears on Shanghai Electric’s website under that name), and it featured the exact same drivetrain concept as the EW 4MW-136. Years later, the licensing deal expanded to include Direct Drive technology, up to 8 MW.

In summary, the EW 4MW-136 turbines at this Croatian wind farm are “siblings” of the SWT 4.0-130, a best-selling, highly reliable turbine whose first prototype was installed back in 2012.

Today, Shanghai Electric and SGRE no longer have any licensing agreement, and the Chinese company develops its own turbines using hybrid drive technology.

Thank you very much for reading Windletter and many thanks to Tetrace, RenerCycle and Nabrawind our main sponsors, for making it possible. If you liked it:

Give it a ❤️

Share it on WhatsApp with this link

And if you feel like it, recommend Windletter to help me grow 🚀

See you next time!

Disclaimer: The opinions presented in Windletter are mine and do not necessarily reflect the views of my employer.